Read These Books if You Like Chocolate (Or Drink Coffee)

You're Friendly Neighborhood Geographer's Guide to The Foods We Love

Hello everyone,

This week, I wanted to highlight some books the Source of Flavor team have been reading—not only to research the crops we’re interested in, but also to get inspiration on how we can apply remote sensing techniques to explore how geography, climate, and the producers who grow it, affect flavor. They are:

Coffeeland by Augustine Sedgewick

Banana by Dan Koeppel

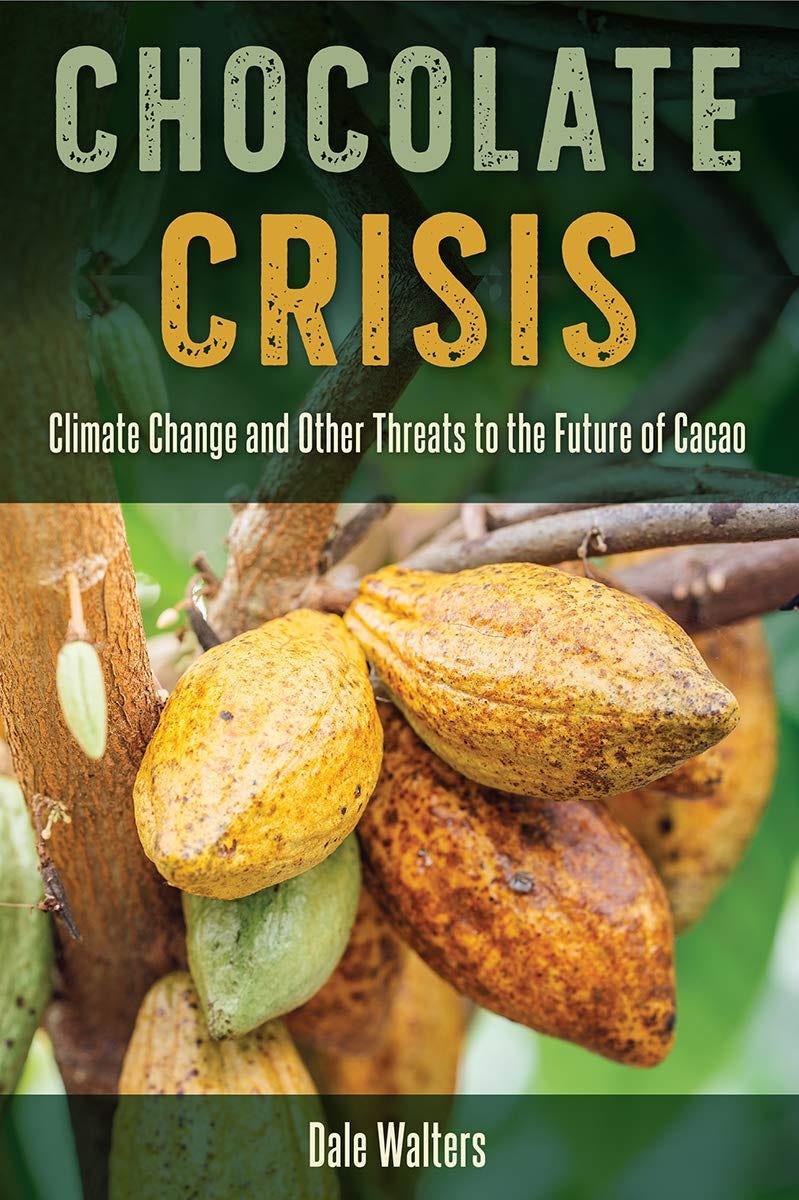

Chocolate Crisis by Dale Walters

Let’s dig in.

☕ Coffeeland by Augustine Sedgewick: Labor, Empire, and the Economics of Stimulation

Sedgewick’s Coffeeland peels back the layers of El Salvador’s coffee empire, tracing how a single plantation became a fulcrum of global trade and control.

From the perspective of a food geographer, what’s striking is how Coffeeland turns the plantation into a node in a global infrastructure of productivity. Coffee becomes a tool to manage bodies and economies—from exhausted factory workers in the U.S. to impoverished laborers in Central America. Sedgewick connects colonial land dispossession, monoculture landscapes, and economic dependency with the click of a Keurig machine.

And as someone who's more of a tea person myself, Sedgewick’s book made me care more—deeply, urgently—about this native Ethiopian plant. After reading it, I felt compelled to explore the landscapes where coffee is grown, and I even wrote a script in Google Earth Engine to generate an NDVI time series to visualize the growing season over time in coffee-growing regions. That’s the impact this book had on me.

🍌 Banana by Dan Koeppel: The Monoculture Fruit That Became a Flashpoint of Globalization

Bananas are a joke, right? Funny shape, slips, lunchboxes. But Koeppel shows you the joke is on us. They are cloned. They are fragile. They are deeply, disturbingly powerful.

It is part botanical detective story, part corporate exposé. He dives into how a sterile, cloned fruit—the Cavendish banana—became the world’s most popular and most endangered produce. The book traces the United Fruit Company’s colonial exploits, the banana republics it helped shape, and the fragile biology behind this globally traded crop. Koeppel’s framing of the banana as a monoculture cautionary tale feels urgent. He illuminates how this fruit’s geographic spread was inseparable from military coups, labor suppression, and environmental degradation. The consumer learns that this cheap, ubiquitous snack was (and perhaps still is) sustained by systems of exploitation—and that a single soil fungus could end it all.

After reading this book, I started purchasing only organic bananas—not necessarily for the health benefits, but more so for workers’ safety. Organic farms tend to create conditions that are safer, with fewer chemical-related injuries than conventional plantations. Koeppel made me see that consumer choices, however small, can echo across global labor systems.

🍫 Chocolate Crisis by Dale Walters: Cacao and the Slow Burn of Climate Change

This one’s still on my nightstand. I’m working through it. Slowly. But already, it’s got its claws in me.

Cacao is in trouble. Trees are picky. They like specific temperatures. And the world, being what it is, doesn’t care. So the trees die. The fungus moves in. The farmers suffer. The chocolate gets more expensive. Or disappears.

What Walters does best is lay out the system without flinching. You get the science: cacao's narrow temperature window, its susceptibility to diseases like frosty pod rot and witches' broom. You get the agronomy: the fragile genetics of cacao, how little diversity exists in the global supply, how it's all a house of cards balanced on West African labor. You also get the market. How a few multinational corporations control most of the trade. How smallholder farmers—especially in Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire—carry the burden of climate risk and get none of the chocolatey glory.

Even mid-read, I couldn’t help myself. I launched another Earth Engine project. Temperature thresholds, West Africa, how many days are too hot for cacao to live. Turns out, it’s a lot.

Walters doesn’t write to guilt you out of your chocolate. He writes to make you see it clearly. He gives you a roadmap of what's broken—and hints at what might be fixed if we pay attention. It’s a book about trees, yes. But it’s also about justice, biodiversity, economics, and the very future of pleasure.

These books are maps. Not of places, but of systems. Invisible scaffolding that holds up the lie that your breakfast is simple. It is not. It is a miracle.

But listen—this isn’t meant to scare you off your favorite foods. Not at all.

Keep eating your chocolate. Keep peeling your bananas. Brew that coffee, or steep that tea. Just maybe do it with a little more awareness. A little more appreciation. A little more wonder. After all, it took a whole world to bring that flavor to your tongue.

And as always, stay curious.

Mina